Writing a new story.

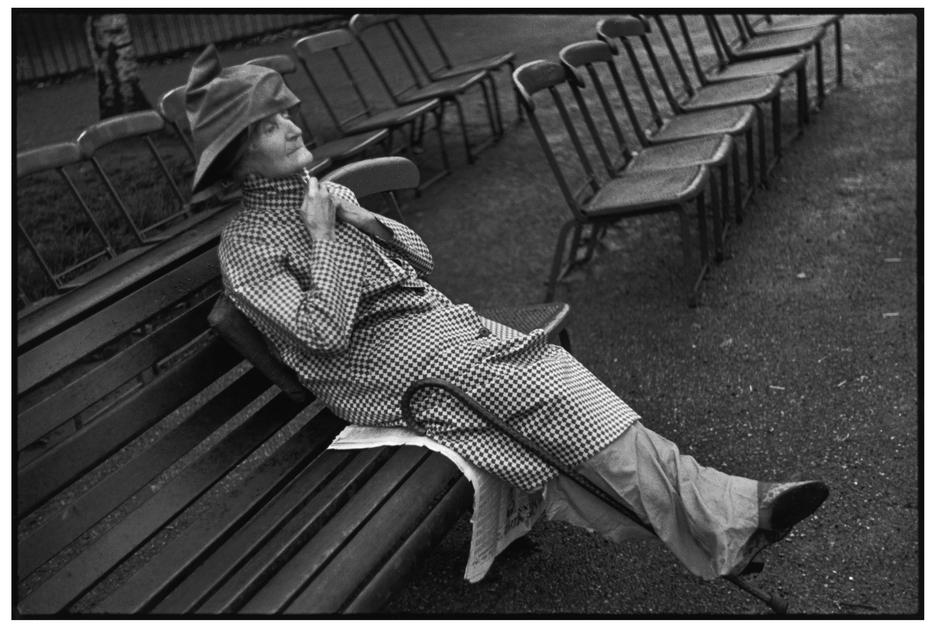

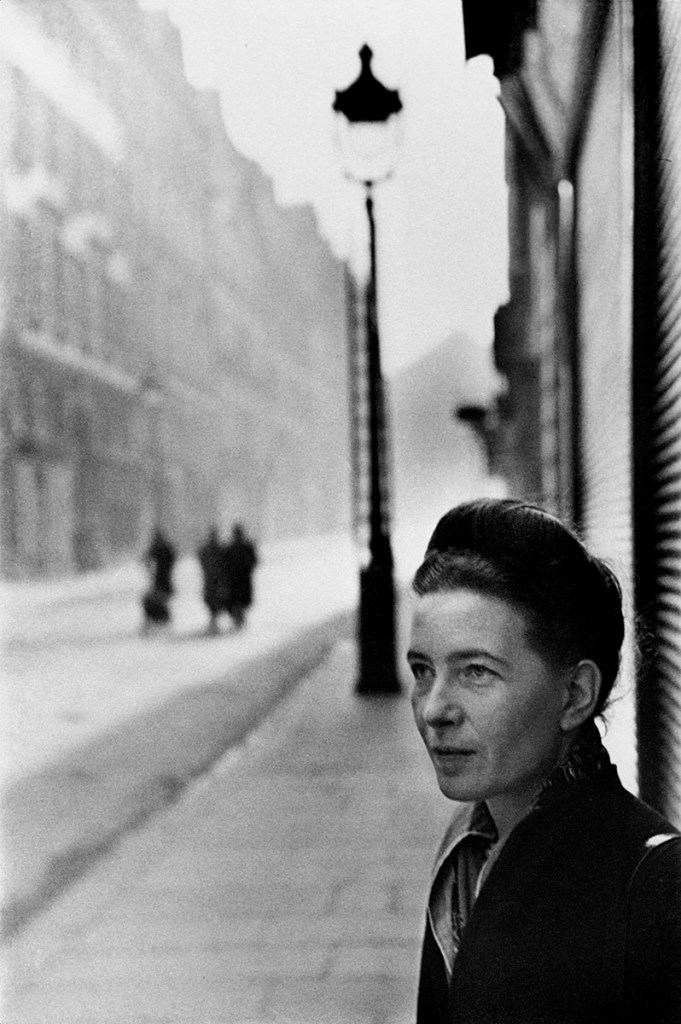

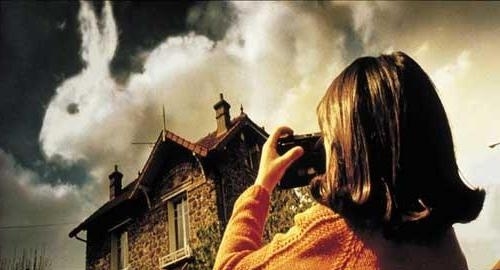

A journey through Paris following the work of famous Paris artists

like Henry Cartier Bresson

A story about getting unwell.

About losing direction and hope, about imagining

that we have let ourselves and everyone down

But it is also a story about getting better.

About regaining the thread, rediscovering meaning

And finding a way back to connection and joy.

I follow the arc of a hero’s or heroine’s journey, from

challenge to freedom. The moment we realize we cannot

cope; the acts of self-care in which we find respite;

and the day we finally reclaim a sense of stability.

Written with understanding and kindness, it is both

a source of companionship in our loneliest moments –

whether we’re experiencing a relationship breakdown,

a career setback, a health crisis or anxiety around the

everyday – and a practical guide that will help us find

reason for hope.

We are all on our own hero’s or heroine’s journey towards

being more authentic. This story will help us along the way.

Join Peter for a truly transformational vacation for the mind.

Practical Info

The price of this three day tour with Peter de Kuster is Euro 2.850 excluding VAT

You can reach Peter for questions about dates and the program by mailing him at peterdekuster@hotmail.nl

TIMETABLE

09.40 Tea & Coffee on arrival

10.00 Morning Session

13.00 Lunch Break

14.00 Afternoon Session

17.00 Drinks

About Peter de Kuster

Peter de Kuster is the founder of The Hero’s Journey & The Heroine’s Journey project, a storytelling firm which helps creative professionals to create careers and lives based on whatever story is most integral to their lives and careers (values, traits, skills and experiences). Peter’s approach combines in-depth storytelling and marketing expertise, and for over 20 years clients have found it effective with a wide range of creative business issues.

Peter is writer of the series The Heroine’s Journey and Hero’s Journey books, he has an MBA in Marketing, MBA in Financial Economics and graduated at university in Sociology and Communication Sciences.

Part I. The Challenge

If we are lucky, when it feels impossible to carry on any longer we will know to put up the white flag at once. There is nothing shameful or rare in our condition; we have fallen ill, as so many before us have. We need not compound our sickness with a sense of embarassment. This is what happens when one is a delicate human facing the hurtful, alarming and always uncertain conditions of existence. Recovery can start the moment we admit we no longer have a clue how to cope.

The roots of the crisis almost certainly go back a long way. Things will have not been right in certain areas for an age, possibly for ever. There will have been grave inadequacies in the early days, things that were said and done to us that should never have been, and bits of reassurance and care that were ominously missed out. In addition to this, adult life will have layered on difficulties which we were not well equipped to know how to endure. It will have applied pressure along our most tender, invisible fault lines.

Our breakdown is trying to draw attention to our problems, but it can only do so inarticularly, by throwing up coarse and vague symptoms. It knows how to signal that we are worried and sad, but it can’t tell us what about and why. That will be the work of patient investigation of your story. The breakdown contains the cure, but it has to be teased out and its original inarticulate story interpreted. Something from the past is crying out to be recognized and will not leave us alone until we have given it its due.

It may seem – at points – like a death sentence but we are, beneath the crisis, being giving an opportunity to restart our lives on a more generous, kind and realistic footing. There is an art to having a breakdown – and to daring at least to listen to what our pain is trying to tell us.

Mental health is a miracle we are apt not to notice until the moment it slips from our grasp – at which point we may wonder how we ever managed to do anything as complicated and beautiful as order our story sanely and calmly.

A mind in a healthy state is, in the background, continually writing a near-miraculous set of stories that underpin our moods of clear-sightedness and purpose. To appreciate what a mental healthy story involves – and therefore what makes up its opposite – we should consider some of what will be happening in the folds from an optimally functioning inner storytelling mind:

- First and foremost, a healthy mind is an editing mind, an organ that manages to sieve, from thousands of stray, dramatic, disconcerting or horrifying stories, those particular ones and sensations that actively need to be entertained in order for us to direct our lives effectively.

- Partly this means keeping at bay punitive and critical judgements that might want to tell us repeatedly how disgraceful and appalling we are – long after harshness has ceased to serve any useful purpose. When we are taking someone one a date, a healthy inner storyteller doesn’t force us to listen to voices that insist on ourunworthiness. It allows us to talk to ourselves as we would to a friend.

- At the same time, a healthy inner storyteller resists the pull of unfair comparisons. It doensn’t constantly allow the achievements and successes of others to throw us off course and reduce us to a state of bitter inadequacy. It doesn’t torture us by continually comparing our condition to that of people who have, in reality, had very different upbringings and trajectories through life. A well-functioning storytelling mind recognizes the futility and cruelty of constantly finding fault with its own nature.

- Along the way, a healthy inner storyteller keeps a judicious grip on the drip, drip, drip of fear. It knows that, in theory, there is an endless number of things that we could worry about; a blood vessel might fail, a scandal might erupt, the plane’s engines could sheer from its wings… But it has a good sense of the distincition between what would conceivably happen and what it is in fact likely to happen, and so it is able to leave us in peace as regards the wilder eventualities of fate, confident that awful things will either not unfold or could be dealt with ably enough if ever they did so. A healthy inner storyteller avoids catastrophic imaginings; it knows that there are broad and stable scenes, not a steep and slippery slope, between itself and disaster.

- A healthy inner storyteller has compartments in their story with heavy doors that shut securely. It can compartmentalize when it needs to. Not all thoughts belong at all moments. While talking to a grand mother, the mind prevents the emergence of images of last night’s erotic fantasies; while looking after a child, it can repress its more cynical and misanthropic analyses. A healthy inner storyteller has mastered the techniques of censorship.

- A healthy inner storyteller can quieten its own buzzing preoccupations in order, at times, to focus on the world beyond itself. It can be present and engaged with what and who is immediately around. Not everything it could feel has to be felt at every moment.

- A healthy inner storyteller combines an appropriate suspicion of certain people with a fundamental trust in humanity. It can take an intelligent risk with a stranger. It doesn’t extrapolate from life’s worst moments in order to destroy the possibility of connection.

- A healthy inner storyteller knows how to hope; it identifies and then hangs on tenaciously for a few reasons to keep going. Grounds for despair, anger and sadness are, of course, all around. But the healthy mind knows how to bracket negativity in the name of endurance. It clings to evidence of what is still good and kind. It remembers to appreciate; it can – despite everything – still look forward to a hot bath, some dried fruit or a satisfying day of work. It refuses to let itself be silenced by all the many sensible arguments in favor of rage and despondency.

Outlining some of the features of a healthy inner storyteller helps us identify what can go awry when we fall ill. At the heart of mental illness is a loss of control over our own better thoughts and feelings. An unwell inner storyteller can’t apply a filter to the information that reaches our awareness; it can no longer order or sequence its content. And from this, any number of painful scenarios ensue:

- Ideas keep coming to the fore that serve no purpose, unkind voices echo ceaselessly. Worrying possibilities press on us all at once, without any bearing on the probability of their occurence. Fear runs riot.

- Simultaneously, regrets drown out any capacity to make our peace with who we are. Every bad thing we have ever said or done reverberates and cripples our self-esteem. We are unable to assign correct proportions to anything: a card that gets lost feels like a conclusive sign that we are doomed; a slightly unfriendly remark by a collague becomes proof that we shouldn’t exist. We can’t grade our worries and focus in on the few that might truly deserve concern.

- We can’t temper our sadness. We can’t overcome the idea that we have not been loved properly, that we have made a mess of the whole of our working lives, that we have disappointed everyone who ever had a shred of faith in us.

- Every compartment of the mind is blown open. The strangest, most extreme thoughts run unchecked across consciousness. We begin to contemplate extreme actions like taking on 6 morfine plasters and a bottle of cognac.

- In the worst cases, we lose the power to distinguish outer reality from our inner world. We can’t tell what is outside us and what inside, where we end and others begin; we speak to people as if they were actors in our own dreams.

- At night, such is the hefty storytelling and the ensuing exhaustion that we become defenceless before our worst apprehensions. By 3 hour clock in the night, after hours of rumination, doing away with ourselves no longer feels like such a remote or unwelcome notion.

However dreadful this inner storytelling sounds, it is a paradox that, for the most part, mental flawed storytelling doesn’t tend to look from the outside as dramatic as we think it should. The majority of us, when we have an internal flawed story, will not be foaming at the mouth or insisting that we are Napoleon. Our suffering will be quiteter, more inward, more concealed and more contiguous with societal normas; we’ll sob mutely into the pillow or dig our nails silently into our palms. Others may not even realize for a very long time, if ever, that we are in difficulty. We ourselves may not quite accept the scale of our sickness.

A flawed inner storyteller is ultimately as common, and as essentially unshameful, as its bodily counterpart – and also comprises a host of more minor ailments, the equivalents of cold sores and broken wrists, abdominal cramps or ingrowing toenails.

When we define a flawed inner storyteller as a loss of command over the mind, few of us can claim to be free of all instances of flawed inner storytelling. True healthy inner storytelling involves a frank acceptance of how much unhealthy storytelling there will have to be even in the most ostensibly competent and meaningful lives. There will be days when we simply can’t stop crying over someone we have lost. Or when we worry so much about the future that we wish life would end right now. Or when we feel so sad that it seems futile even to open our mouths. We should at such times be counted as no less ill than a person laid up in bed with flu – and as worthy of attention and sympathy.

It doesn’t help that we are at least a hundred years away from properly fathoming how the brain operates – and how it might be healed. We are in the mental arena roughly equivalent to where we might have been in bodily medicine around the middle of the seventeenth century, as we slowly built up a picture of how blood circulated around our veins or our kidneys functioned. In our attempts to find fixes we are akin to those surgeons depicted in early prints who cut up cadavers with rusty scissors and clusily dug around the innards with a poker. We will – surpisingly – be well on the way to colonizing Mars before we definitively grasp the secrets to the workings of our own minds.

This journey through Paris aims to be a sanctuary where we can sit once in a while and recover our strength, in an atmosphere of kindness and fellow feeling. It outlines a raft of storytelling moves with which we might approach our most stubborn unhealthy inner storytelling and instabilities. It sets out to be a friend through some of the most difficult moments of our lives.

Our societies sometimes struggle with the question of what stories in art, literature, film might be for. Here the answer feels simple: stories are a weapon against despair. They are tools with which to alleviate a sense of crushing isolation and uniqueness. It provides common ground where the sadness i n me can, with dignity and intelligence, meet the sadness in you.

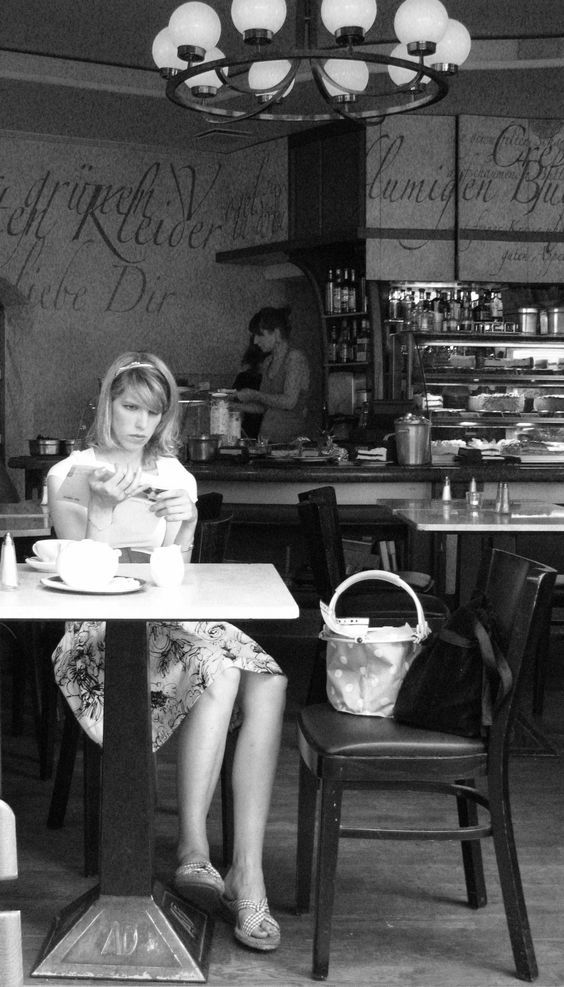

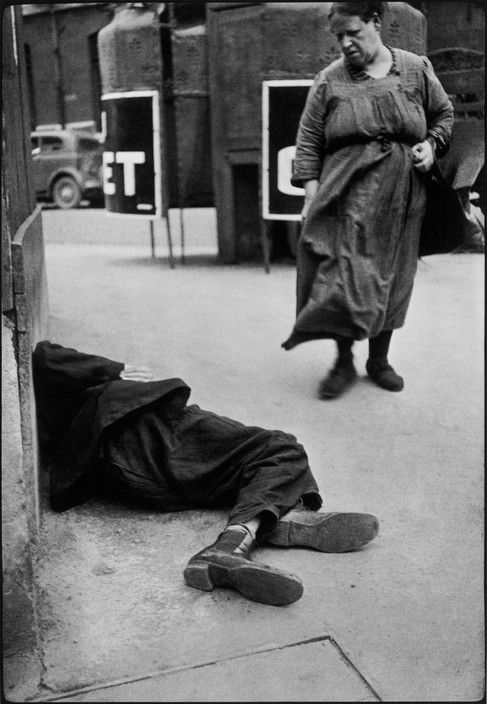

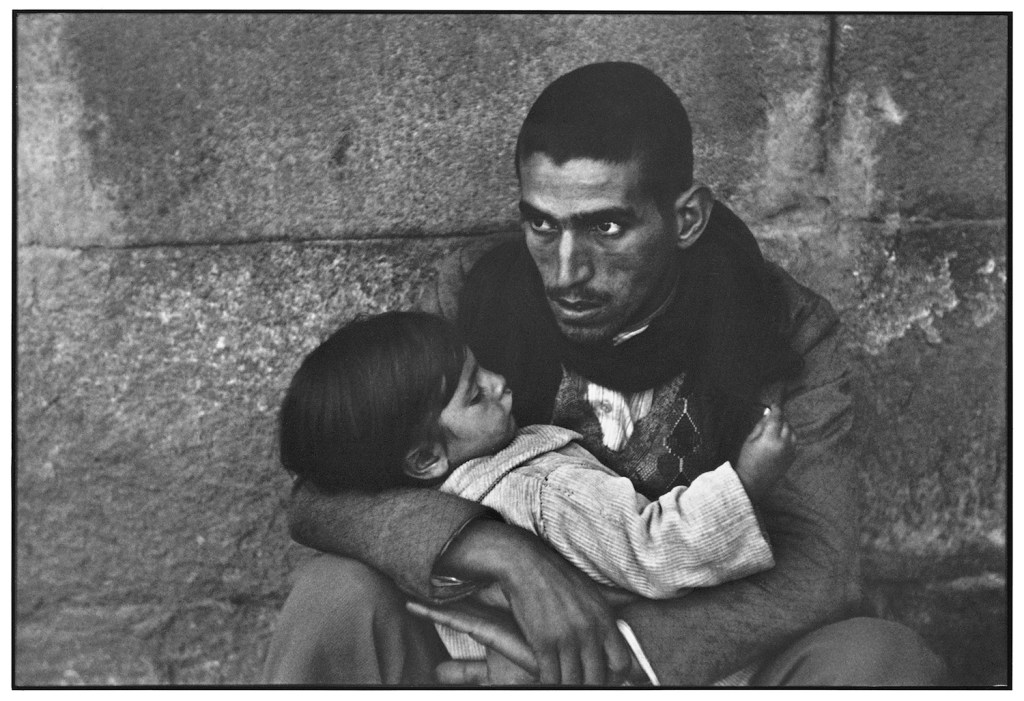

Perhaps for a long tie, the man in the diner kept it together. As late as this morning, he might have believed that, despite everything he would be OK. He’d taken his hat along with him, as always he remained attached to appearances. Even as his anguish mounted, he kept going, one sip of coffee after another, an ocassional par of the mouth with a paper napkin, while looking at the busy room: secretaries at lunch, people from the nearby construction site, a few exhausted mothers and their kids. Then suddenly, there was no more arguing with the despair any longer. It swept him up without a chance of a rejoinder: the mess he had made, the fool he had become in everyone’s eyes, the absurdity of everything. His head hit the table with a shocking clatter but almost at once it was absorbed by the dense murmur of the room and the city. One could die in public here and few would notice.

Except that there was a French photographer right opposite who was very much into noticing everyting: an elegant, willowy man, with a name impossible for Americans to pronounce – he invited him to call him Harry – and a Leica 35 around his neck. Henri Cartier-Bresson had wandered the area all morning; he’s shot a group of women chatting outside on Ground Street and discovered a striking view of midtown Manhattan from the promenade. He had just begun his lunch, when, without warning, there came that distinctive bang of a heat hitting a table with force.

We need not feel ashamed, the photograph suggest, that we are in despair; it is an inevitable part of being alive. The distress that normally dwells painfully and privately inside our minds has been given social expression – and no longer needs to be shouldered alone. Whatever a distressingly upbeat world sometimes implies, it is normal, very normal, to be in agony. We don’t, on top of it all, ever need to feel unique for being unwell.

CURLING UP INTO A BALL

We cause ourselves a lot of pain by pretending to be competent, all-knowing, proficient adults long after we should,ideally, called for help. We suffer a bitter rejection in love, but tell ourselves and our acquaintances that we never cared. We hear some wounding rumours about us but refuse to stoop to our opponents’ level. We find we can’t sleep at night and are exhausted and anxious in the day, but continue to insist that stepping aside for a break is only for weaklings.

We all originally came from a very tight ball-like space. For the first nine months of our existence, we were curled up, with our head on our knees, protected from a more dangerous and colder world beyond by the position of our limbs.

In our young years, we knew well enough how to recover this ball position when things got tough. If we were mocked in the playground or misunderstood by a snappy parent, it was instinctive to go up to our room and adopt the ball position until matters started to feel more manageable again. Only later, around adolescence, did some of us lose sight of this valuable exercise in regression and thereby began missing out on a chance for nurture and recovery.

Dominant ideas of what can be expected of a wise, fully mature adult tend to lack realism. Though we may by twenty – eight or forty – seven on the outside, we are inevitably still carrying within us a child for whom a day at work will be untenably exhausting, a child who won’t be able to clam down easily after an insult, who will need reassurance after every minor rejection, who will want to cry without quite knowing why and who will fairly regularly require a chance to be ‘held’ until the sobs have subsided.

It is a sign of the supreme wisdom of small children that they have no shame or compunction about bursting into tears. They have a more accurate and less pride-filled sense of their place in the world than a typical adult: they know that they are extremely small beings in a hostile and unpredictable realm, that they can’t control much of what is happening around them, that their powers of understanding are limited and that there is a great deal to feel distressed, melancholy and confused about.

As we age, we learn to avoid being, at all cost, that most apparently repugnant – and yet in fact deeply philosophical – of creatures: the crybaby. But moments of losing courage belong to a brave life. If we do not allow ourselves frequent occasions to bend, we will be at far greater risk of one day fatefully snapping.

When the impulse to cry strikes, we should be grown up enough to cede to it as we did in our fourth or fifth years. We should repair to a quiet room, put the duvet over our head and allow despondency to have its way.

There is in truth no maturity without an adequate negotiation with the infantile and no such thing as a proper grown – up who does not frequently yearns to be comforted like a toddler.

If we have properly sobbed, at some point in the misery an idea – however minor – will at last enter our mind and make a tentative case for the other side: we’ll remember that it would be quite pleasant and possible to have a very hot bath, that someone once stroked our hair kindly, that we have one and a half good friends on the planet and an interesting book still to read – and we’ll know that the worst of the storm may be ebbing.

THE MONSTERS IN PARIS WHO ARE WATCHING US

When we travel Paris during the day we feel so-called monsters hovering over us. In the night monsters might haunt us too. We can fend the animals off with rational arguments. off course we’ve done nothing wrong. There is no reason to keep apologizing. We have the right to be. To create. But at night, we can forget all weapons of self defence. Why are we still alive? Why haven’t we given up yet? We don’t know what to answer any more.

To survive mentally, we might need to undertake a lengthy analysis of where the monsters come from, what it feeds off, what makes it go on the prowl and how it can be wrestled into submission. One monster might have been born from our father’s mouth, another from our mother’s neglect. Most of them get excited when we have too much work, when we’re exhausted and when the city we live in is at its most frenetic. And they hate early nights, nature and the love of friends.

We need to manage our monsters – each of us has our own versions – with all the respect we owe to something that has the power to kill us. We need to build very strong cages out of solid, kind arguments against them. At the same time, we can take comfort from the idea that the night – time monsters will get less vicious the more we can lead reasonable, serene lives. With enough gentleness and compassion, we can hope to reach a point when, even in the dead of night, as these monsters appear, we will remember enough about ourselves to be unafraid and to know that we are safe and worthy of tenderness.

The monsters hoovering above Paris are not just an evocation of terror; they are also pointing us – more hopefully – to how we might in time tame our monsters through love and reason.

REASONS TO LIVE

When we say that someone has fallen mentally ill, what we are frequently indicating is the loss of long-established reasons to remain alive. And so the tassk ahead is to make a series of interventions, as imaginative as they are kind, that could – somehow – return the unfortunate sufferer to a feeling of the value of their own survival.

This cannot, of course, ever be a matter of simply telling someone in pain what the answers are or of presenting them with a ready – made checklist of options without any sincere or subtle connectioins with their own character. If we are to recover a true taste for life, it can only be on the basis that others haven been creative and accommodating enough to learn the particularities of our upsets and reversals and are armed with a sufficiently complicated grasp of how resistant our minds can be to the so-called obvious and convenient solutions.

We can hang on to one essential and cheering thought: that no life, whatever the apparent obstacles, has to be extinguished. There are invariably ways for it to be rendered liveable again; there are always reasons to be found why a person, any person, might go on. What matters is the degree of perseverance, ingenuity and love we can bring to the taask of rewriting their own story.

Most probably, the reasons why we will feel we can live will look very different after the crisis compared with what they were before. Like water that has been blocked, our ambitions and enthusiasms will need to seel alternative channels down which to flow. We might not be able to put our confidence in our old social circle or occupation, our partner or our way of thinking. We will have to create new stories about who we are and what counts. We may need to forgive ourselves for errors, give up on a need to feel exceptional, surrender worldly ambitions and cease once and for all to imagine that our minds could be as logical or as reliable as we had hoped.

If there is any advantage to going through a mental crisis of the worst kind, it is that – on the other side of it – we will have ended up choosing life rather than merely assuming it to be the unremarkable norm. We, the ones who have crawled back from the darkness, may be disadvantaged in a hundred ways, but at least we will have had to find, rather than assumed or inherited, reasons why we are still here. Every day we continue will be a day earned back from death, and our satisfactions will be all the more intense and our gratitude more profound for having been consciously arrived at.

WHAT IS YOUR STORY?

One of the great impediments to understanding our lives properly is our automatic assumption that we already do so. It’t easy to carry around with us, and exchange with others, surface intellectual descriptions of key painful events that leave the marrow of our emotions behind. We may say that we remember, for example, that we didn’t get on too well’ with our father, that our father was ‘slightly neglectful’ or that going to school was a ‘boring’.

It could, on this basis, sound as if we surely have a solid enough grip on events. but these compressed stories are precisely the sort of readymade, affectless accounts that stand in the way of connecting properly and viscerally with what happened to us and therefore of knowing ourselves adequately. If we can put it in a paradoxical form, our memories are what allows us to forget. Our day-to-day accounts may bear as much resemblance to the vivid truth of our lives as a big part of mythology does.

If this matters, it’s because only on the basis of proper immersion in past fears, sadnesses, rages and losses can we ever recover from certain disorders that develop when difficult events have become immobilized within us. To be liberated from the past, we need to mourn it, and for this to occur, we need to get in touch with what it actually felt like. We need to sense, in a way we may not have done for decades, the pain of our brother or sister preferred to us or the devastation of being maltreated in the study on a Saturday morning.

The difference between felt and lifeless memories could be compared to the difference between a mediocre and a great sculpture. Both will show us an identifable situation, but only a great sculptor will properly seize, from among millions of possible elements, the few that really render the moment charming, interesting sad or tender. In one case we know about this situation, in the other we can finally feel it.

This may seem like a narrow aesthetic consideration, but it goes to the core of what we need to do to recover from psychological complaints. We cannot continue to fly high over the past in our jet plane while refusing to re-experience the territory we are crossing. We need to get out and walk, inch by painful inch, through the swampy realities fo long ago. We need to close our eyes and endure things, methaphorically on foot. Only when we have returned afresh to our suffering and know it in our bones will it ever promise to leave us alone.

FIGURING OUT WHAT OUR REAL STORY IS

Our real story, what we really think about, for example our character or the next best move we should make in our career or our stance towards an incident in our society … all of our conclusions on such critical topics can remain locked inside us, part of us but inaccessible to ordinary consciousness. We operate instead with surface and misleading pictures of our dispositions and goals. We may settle, in haste or fear, on the most obvious stories: our new friend is very attentive, we should aim for the most highly paid position.

We ignore our truths first and foremost because we aren’t trained to solicit them; no one ever quite tells us that we might need to exhibit the patience and wiliness of an angler while waiting at the riverbank of the deep mind. We’ve been brought up to act fast, to assume that we know everything immediately and to ignore the fact that consciousness is made up of layers, and it is the lower strata that might contain the richest, most faithful material. We may also be hesistant because the answers that emerge from any desent into the depths and subsequent communion with our inner beings can sound at odds with the settled expectations we have of ourselves in daylight. It might turn out that in fact we don’t love who we’re meant to love, or are scared and suspicious of someone who is pressing us to trust them or are deeply moved by, and sympathetic to, a person we hardly know. It’s the profoundly challenging nature of our conclusions that keeps us away from our inner sanctum. We prioritize a sense of feeling normal over the jolting realizations of the true self.

The steps we need to take in order to check in with ourselves are not especially complicated. We must make time, as often as once a day, to lie very still on our own somewhere, probably in bed or maybe in bath, to close our eyes and direct our attention towards one of many tangled or murky topics that deserve reflection: a partner, a work challenge, an invitation, a forthcoming trip, a relationship with a child or a parent. We might need a moment to locate our actual concern. Then, disengaged from the ordinary static, we should circle the matter and ask ourselves with unusual guilelessness: What is coming up for me here? Holding the partner, work challence, invitation or disagreement patiently in mind, we should whisper to ourselves: What do I really think? What is the real issue? What is truly going on? What is actually at stake?

We should – to sound a little soft-headed – ask ourselves what story our heart is whispering to us or what story our gut is trying to articulate. We’re striving to access a sincere part of the mind too often crushed by the barking, harried commands of the conformist executive self. What we will almost certainly find is that, in a quasi-mystical way, the answers are already there waiting for us, like the stars that were present all along and only required the sun to fade in order to come to light in the dome of the sky. We already know – much more accurately than we ever assume – who we should be friends with, what is good and bad for us, and what our purpose on this earth is.

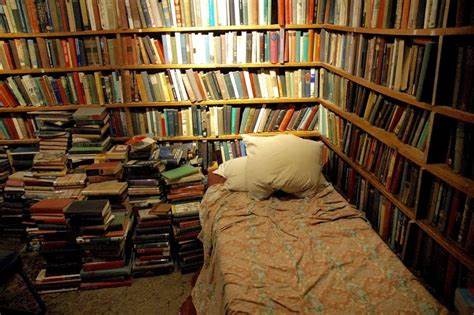

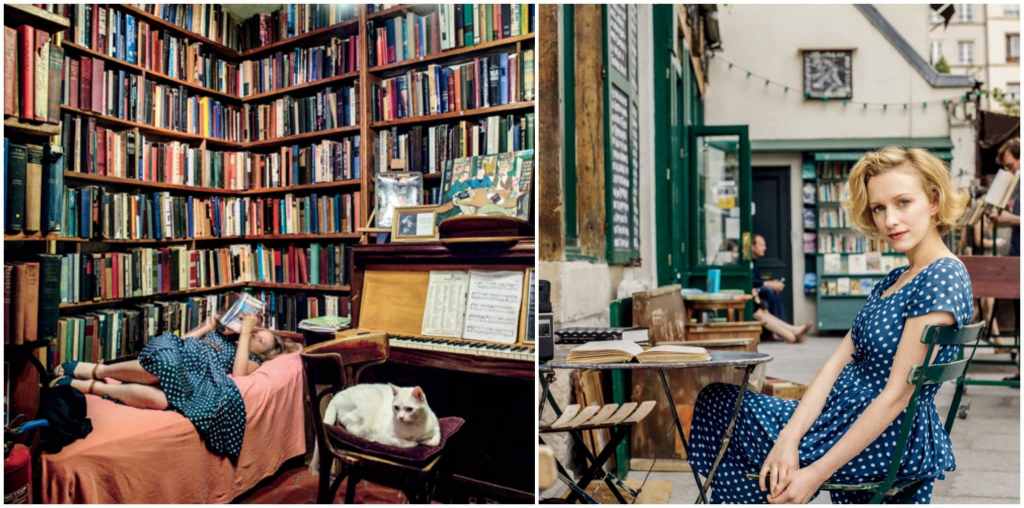

the famous bed in bookstore shakespeare & company Paris

We need only a few moments in the dark at 11 p.m. or 5 a.m. to wander the corridors of the deep mind with the torch of consciousness and ask: What have I looked at but never seen?

FACING ANXIETY

One of the stranger aspects of feeling anxious is that we can be both suffering and markedly uninclined or unable to acknowledge that we are in fact so. We know of course that something isn’t quite right,but a kind of bravery or pride keeps us running forward, unable to square up to the problem. It’s as if, somewhere in our thoughts, we worry that looking at our anxiety directly will bring us harm: slow us down, cause us pain or just be of no use.

It helps us to note that our minds can easily carry more than one mood. They are like cinemas with a variety of screens; there tends to be a foreground and a background to our emotional horizon in which very different things may be happening. In the foreground we might – on a given day – be focused on achieving certain practical goals. Things might be fast – paced and relentness. We might keep opening tabs, scanning the diary, looking up emails – and diverting ourselves with glimpses at the news.

But then at another level, further back in the emotional sky, there might be something vast, eerie and confused, a black sun we can’t quite see or touch and yet also can’t escape from. It tracks us everywhere; it is never not present but it doesn’t ever clarify itself into anything with borders. If it had a book cover it might be about fear and doom.

It isn’t, of course, very pleasant to be bearing this sort of diffuse anxiety within us. But we are not powerless before it and the way to defeat it is, paradoxially, to engage with it more directy than we probably have to date. Doing so is both easy and hard. Practically speaking, it requires nothing more than a few questions, questions which sound – at one level – utterly banal in their simpicity. But though such simplicity can be an insult to our pride, we should never do ourselves the injustice of assuming that our misery rests on something overly complex at a procedural level. We should be humble in the face of the ostensibly simple things that can ruin our lives.

With this caveat, we should step outside the ordinary flow of the anxious day for a moment, close our eyes, take a deep breath and ask ourselves this: What am I really worried about right now? If we let the question resonate for a time, allowing its true profundity to emerge, we stand to find that, waiting until we have quietened the noise, there is a pain we knew all along, looking up at us with startled, wise eyes.

We can continue the questioning: Why is this thing so worrying?

And then: What could I tell myself for a story to make this less bad?

And finally, we can ask ourselves to complete a sentence: I feel compassion for myself because ….

It sounds so simple and it takes only a few minutes, but it can decisively change the internal weather. Our minds are not obvious to themselves. We may be running for days, months, decades even, without pausing to wonder what is really the matter. We have so much misplaced composure, it can be dreadful to realize how fragile and scared we have been all along. We need to create a small safe place in which we can ask ourselves some basis questions – and whisper to ourselves what we are truly finding difficult.

CHILDHOOD

Modern psychotherapy is united on one point: our problems require us to engage with our childhoods. This can feel profoundly offensive. How insulting to be told that childhood could matter inordinately in our adult lives, to our temperament, our chances of happiness, our sexuality, our levels of anxiety and our self-esteem. Particularly if our childhood was difficult, we want more than anything to escape its dark centrifugal energy and to imagine ourselves as a free agent, able to determine the future without impediment. How dispiriting to be asked to believe that who we are was substantially determined by external factors before we reached the age of reason and, moreover, that if we are to h ave any hope of helping ourselves, we must undertake a painful and lenghty journey to understand the past in fine-grained detail.

It is clear why we might want to take out our annoyance on psychotherapy itself. Has this discipline not seen how broad and interesting the world is? How many grand and strange things there are in it? Hasn’t it soared the world? Why does it so badly want us to return to, and circle, the messy claustrophobic start?

We understand. To take on the past, we don’t need to be driven by a preternatural enthusiasm for self-exploration, we don’t need to be self-pitying or dementedly furious with parents who were only trying to do their best. All that is required is a weary, dutiful realization that the principal way to overcome our history is to adress it. We hould try to remember not out of nostalgia, but in order to be able to forget once and for all.

COULD IT MATTER SO MUCH?

Our unwillingness to look backwards might have to do with more than just boredom or frustration; it might be a symptom of sheer incredulity that childhood could matter as much as it apparently does. Could this period be so critical? Could events in those short years have such an outsize influence on everything that comes after? Are children really so impressionable and easily marked?

The short answer to all such enquiries is a weary, regretful but resounding yes. The human mind between the ages of one and ten is dauntingly receptive, infinitely attuned to its environment, which means that our whole identity can be decisively and near-permanently shaped by our young experiences. A somewhat cold, forbidding father or an erratic mother really may be all that is required to breed an elevated degree of anxiety or self-hatred that colours the next eight decades. This susceptibility has been present throughout history, but only now are we beginning to notice it and give it due attention. Every era had its share of childhood-damaged people, it’s just that no one bothered to find out why the neighbour was so sad, the merchant fell into rages or the knight was impotent – just as no one bothered to investigate what might pollute water or how germs could spread. We are, finally, becoming a little more aware of causes and effects.

In insisting on the importance of the early years, it can help to think of the acquisition of language. Without having any memory of the phenomenon, all of us learned – between the ages of zero and five – many thousands of words and their seemingly limitless combinations. While we were innocently going about our business a part of our minds was picking up and assembling, with extraordinary ingenuity, entire dictionaries of terminologies and meanings. Without having any clue how it all happened, we became expert grammarians, far surpassing our mightiest computers in dexterity.

We should imagine that something similar was going on in the psychological sphere. We were acquiring an extensive command of storytelling – emotional language: we were learning about trust, communicatioin, esteem, kindness, cruelty, shame, anger, empathy, selfishness and responsibility. And we didn’t realize that this was happening any more than we realized that we were learning to speak. We were simply going about the ordinary business of childhood while being emotionally imprinted in a most permanent and comprehensive way by the people around us using the power of storytelling.

We now spare little time thinking of how relative our emotional language, our storytelling might be, just as we seldom reflect on the arbitrariness of speaking English or French rather than Portugese. Or to shift register, people who don’t feel depressed every time they succeed or worry that any sexual encounter might end in disappointment.

And finally, as with standard language, with time we stand to realize how appallingly hard it can be to learn a new and different language, what a struggle we have ahead of us when we no longer want to speak in our allocated tongue – a tongue of anxiety, self-hatred, contempt and cynism – and seek to try to express ourselves instead in tones of trust, calm and kindness.

THE IMPRESSIONABILITY OF A CHILD

To accept the importance of childhood, we need above all to take on board and inwardly feel the desperate impressionability and vulnerability of a one- or – two – year- old child. Notice, first, their scale. The fingers are implausibly tiny, the wrists even more so. A modest bump to the head or three centimeters of water can finish them off. Notice, too, how out of control they are. Saliva dribbles from their mouth, their head bobs drunkenly when they are weary, they fall asleep in supermarkets or on the laps of near strangers. They’re wholly, terrifyingly trusting. They lack all defences. They take everything at face value. They’ll follow you wherever you want to take them. You can tell them strange stories about who lives in the house next door, or why the trees look the way they do, or what sort of human being you are. And they’ll agree. They have no place from which to judge anything independently. They can’t tell if Mummy is as nice as she claims, they simply know that she has supernatural powers and understands how to drive a car and makes great cakes. They won’t be able to determine whether what Daddy is doing is reasonable or kind until another decade has passed.

The vulnerability is both touching and – when one remembers how damaged certain adults are – appalling. One can do anything with little people. Tell them you are their friend and then burn their hand, give them a lolly and then separate them from their parents, whisper to them late at night that no one must ever know about this and ruin them for life. It sounds highly disturbing and it is.

We were those little people once. We aren’t any longer. We know the ways of the world. We’re tall and our voices carry. We can think freely. But this was once us – and the distortions of those years have a habit of remaining embedded within our minds for a long time, beneath a substratum of maturity. We owe it to ourselves to take a very patient look at what might have happened to us before we knew who we were.

WHAT IS A GOOD PARENT?

We can afford a few generalizations. First, and most importantly, a competent parent is someone who can feel inordinately pleased that their child has come into the world – and never ceases to remind themselves or their offspring of the fact, in direct and indirect ways, at small and large moments, pretty much every day. There is no risk of spoiling anyone by doing so: spoilt people are those who were denied love, not those who had their fill of it.

Second the good parent is attuned to their child; they listen – very closely indeed – to what the small person is trying to say. This means getting down on their knees and paying attention to messages that may sometimes sound extremely weird. Maybe the cild is saying that they are very sad, even though it is their birthday and the parent has gone to enormous troubles with the presents. Maybe they are explaing they are fed up with Granny, though of course she means well and she’s our mother too. Children are filled with complicated emotions that may have no place in the average adult’s assessment of what is ‘normal’, let alone convenient. Good parents suspend judgement and check their certainties. There is no danger of creating an entitled brat by doing so. People who cause a fuss don’t generally do so because they have been listened to a lot; they start screaming – and later taking drugs and robbing shops – because their smaller, ,younger stories were never heard.

A good parent is, furthermore, not so fragile that they constantly need to be obeyed. They can take being sometimes called a fool because they lost their pride long ago. They’re sufficiently on top of the unfairness of life not to mind being someone on whom a child, especially a teenage one, occasionally offloads their disappointments at the misery of everything. They don’t need to instil terror, they have the self-confidence to be ignored or overlooked brusquely when a child’s development requires it.

A good parent isn’t envious of their children. They are strong enough to allow them to have a better life than they did. They aren’t sadists; they never derive relief from making a child miserable They don’t think it is a good idea to make someone very unhappy because someone else made them miserable long ago.

They are sufficiently on top of their issues to be able to warn their children about them. They make it easy for the child to work out what the family madness is – and to move from it. They don’t insist on their normality and then challenge the child to determine where they have been lied to.

They don’t inject their poison into anyone: their jealousy, terror, ambition or disappointment remains a matter for them alone.

They don’t need attention from their own children because they have enough of an audience elsewhere.

They don’t demand admiration – and certainly not gratitude. They know how to be calm and even boring. They absorb the child’s excitements and terrors without adding to them. They show up day after day and act with reliable dullness. Of course they have drama going on beneath the surface, it’s just that no child wants to think of their parent as overly complicated or three-dimensional. The good parent doesn’t mind being, in a benign sense, a caricature.

The good parents knows how to play because their imagination is free: the doll can be a princess, the sofa can be a ship and dinner might be pushed by half an hour without peril. They’re solid enough inside not to need to impose rigidity on the world. Sometimes, they can allow themselves to be very silly.

They know about boundaries. The game was hilarious for a long time, but now it’s the moment to wind down, to put the pains away, to get back to work or to go up to bed. The good parent doesn’t mind being hated for a time in the name of honouring reality.

Around the good parent, the child is, at the same time, allowed to nutter ‘no’ about certain matters, being a centre of sufficient autonomy to disagree. It should not have the final say but should invariably have a voice.

The good parent is tender: of course teddy’s lost eye doesn’t matter in the broad run of things, but the child’s world is small and minor things loom large in it. Good parents therefore have the patience to respond to the child’s minor crises and delights from a sure sense that maturity will emerge through precisely targeted indulgence.

We might think back to our past and give our carers a score to measue how things went. It isn’t unfair or mean sometimes – in the privacy of our own minds – to hold people to account.

WHAT A BAD PARENT CAN DO TO A CHILD

The power of a bad parent is almost without limit. Within only a few years, a bad parent might be able to create an offspring who:

is convinced that they are unworthy

hates themselves without limit

is perpetually certain that they have done something very wrong

constantly anticipates catastrophe

loathes their own appearance

fears everyone’s rage and envy

cannot enjoy sex

is unable to explore their mind

always feels they need to agree, comply and people-please

can’t show their true self for fear of revolting everyone

will never put a stop to their own abuse, in whatever form this comes

has to puff themselves up with money and acclaim to feel acceptable

is complelled to torture others as they were tortured

cannot tolerate ambiguity and criticism

cannot play

must always be right

has to sabotage anything promising, kind and good that enters their life

And that’s just to start the list.

THE PARENT’S WHO LIVE INSIDE OUR MINDS

It’s a measure of how invisible the process of parental imprinting can be that most of us would be highly surprised to think that a parent or two might be living inside our heads. The way we think seems to us to be the result of our own will. We seldom come across any voices or attitudes that feel actively foreign or externally sourced.

Nevertheless, given how long we were exposed to them and at what formative stages, our parents may have left more of a mark on us than we normally recognize and may be constantly commenting on our lives from inside like a chorus of unhelpful marionettes.

When we fail, a voice inside us may say: you can’t do anything right. When a relationship breaks down, an inner voice might whisper: Never expect anything from others. When a nasty rumour spreads about us, we hear: You were always too impulsive.

It can help to ask ourselves a number of questions about our parent’s views – as experience has taught us to conceive of them. We might, without thinking too hard and thereby allowing our defences to choke our spontaneous insights, finish the following sentences:

My father gave me a feeling that I am ….

My mother left me with a sense that I am …

My father would now think that I am ….

My mother would now think that I am …

What our inner parents have to say is often not especially enlightened or in line with what we want for ourselves. And yet even so we can observe how deeply such ideas sink into us.

We can continue the exercise:

If I really needed him, my father…..

If I really needed her, my mother….

To disagree with my father would mean ….

To disagree with my mother would mean ….

If I made a mistake, my father would ….

If I made a mistake, my mother would…

Our parent’s views rarely stick out in our minds. Instead they merge with our own; they lose their identifying labels and become sides of everyday consciousness, indistinguishable from what we more broadly want and believe.

Yet we should try to reverse the process of absorption and recover some distance between ourselves and impulses and atittudes that may bear no relation to our healthier aspirations. It is bad enough to suffer; it is even worse to do so at the hands of what we might as well term, a coven of unfriendly ghosts.

THE EXTREME LOYALTY OF CHILDREN TO THEIR PARENTS

We hear a lot about ungrateful children; offspring who lack respect and deference, who don’t appreciate how much was done for them, who complain without reason and lament with unfair bitterness.

But what is often missed is how deeply children are, for the most part, loyal to their parents. They will go to enormous lengths to try to think well of those who brought them into the world, isolating things that are good in them and focusing on these wholeheartedly at the expense of memorizing what was mean-spirited or painful.

The worse the childhood, the greater and more manic the filial loyalty tends to be. There are no more tenacious defenders of their parents legacies and reputations than those who were maligned, ignored or physically harmed. In a choice between thinking that we might be bad ourselves or accepting that a parent was the disappointing and cruel one, self-hatred tends to win most of the time. It is, in the end, less devastating to deem ourselves ungrateful and awful than to imagine that we were brought up by small minded mediocrities who were too ill or troubled to care.

ARE WE SELF-OBSESSED?

To compound our sense of irritation at needing to look at our childhoods, we may have a nagging sense that doing so is a uniquely modern luxury. It can seem like evidence of a particularly regrettable kind of decadence and weakness that we should be spending so much time thinking of ‘Mummy’ or ‘Daddy’ while outside bigger and more important issues await us. We may enviously suspect that earlier, less cosseted and more martial ages had no time for any such nonsense. They were too busy surviving to indulge themselves in idele, circuitous thoughts about their ancestors and progenitors.

But we should be wary on this score. People in other ages did not know about projection, the superego or repression. And yet they thought a lot about mummies and daddies nonetheless – and worried intensely about the impact they had on their lives. Even while they were spearing enemies, tracking deer or setting off in longboats, they were never far from extraordinary absorption in their own families’ stories. They simply framed their interests in different terms.

In any premodern culture we might study, we can identify an obsession with the well being and management of ‘ancestors’. Every illness, pertubaration of the mind, obsession, incapacity or sorrow will immediately be ascribed to the work of the spirit of a dead family member; it is always about the past. And every society therefore learns to manage these figures from yesteryear with extreme care, with an understanding that an ancestor who has not been properly processed and put to rest will end up taking bitter revenge on us: we might become impotent or grow depressed, marry the wrong person or fail in our careers.

We may not go about matters in exactly the way of our ancestors, but the underlying dynamics are strikingly similar. We are in essence always striving to ensure that figures from our past are not allowed to ruin what remains of our lives.

LOVE

The main ingredient on which any recovery from mental issues depends is also one which, curiously and grievously, never makes an appearance in any medical handbook, namely love. The word is so fatefully associated with romance and sentimentality that we overlook its critical role in helping us to keep faith with life at times of overwhelming psychological confusion and sorrow. Love – whether from a friend, a partner, an offspring or a parent – has an indomitable power to rescue us from mental illness.

We might go so far as to say that anyone who has ever suffered from mental illness and who recovers will do so – whether they consciously realize it or not – because of an experience of love. And, by extension, no one has ever fallen gravely mentally ill without, somewhere along the line, having suffered from a severe deficit of love. Love turns out to be the guiding strand running through the onset of, and recovery from, our worst episodes of unwellness.

What, then, do we mean by love, in its life-giving, mind-healing sense?

UNCONDITIONAL APPROVAL

What frequently assails and derails us when we are sick in our minds is a continuous punishing sense of how terrible we are. We are lacerated by self-hatred. Without any external prompting, we think of ourselves as some of the worst people around, even the worst people on earth. Our own charge sheet against us is definitive: we are ‘awful’, ‘terrible’, ‘nasty’, ‘bad’. We can’t really say much more – and efforts to get us to expand in rational terms may run aground. We often can’t even point to a specific crime, or if we do it doesn’t seem to onlookers quite the energy we devote to it. In our illness, a primal self-suspicion burst through our defences and overtakes our faculties, leaving no room for the slightest gentleness. We are implacably appalled by, and unforgiving of, who we are.

In such agony, a loving companion can make the difference between suicide and keeping going. Such companions do not try to persuade us of our worth with cold reason; nor do they need to go in for any showy displays of affection. they can just demonstrate that we matter to them in a thousand surreptitious yet fundamental ways. They keep showing up by our bed day after day, they make pleasant conversation about something that won’t in any way make us anxious, they’ve remembered a favourite blanket or a drink, they know how to make a few jokes when these help and they suggest a nap when they feel us drifting away. They have a good sense of the sources of our pain, but they aren’t pushing us for a big conversation or confession. They can tolerate how ill we were and will stick by us however long it takes. We don’t have to impress them and they won’t worry too much about how scary we are looking or the weird things we might say. They’re not going to give up ons us. The disease might take a month or six years or sixty, but they’re going nowhere. We can call them at strange hours. We can sob or we can sound very adult and reasonable. They seem, remarkably, to love us in and of ourselves, for who we are rather than anything we do. They hold a loving mirror to us and help us to tolerate the reflection. It’s pretty much the most beautiful and useful thing in the universe.

More to appear in the coming week!